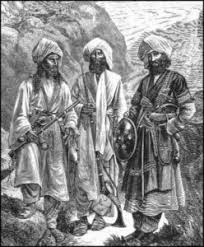

Faqir Of Epi, Ipi Faqir. Haji Mirzali Khan.

The Story of Haji Mirzali Khan of Epi or Faqeer Epi of Waziristan. ( 1897 — April 196 ) also known as Haji Sahib.

The main ‘opponent’ of the British on the Frontier between the two World Wars was the Scarlet Pimpernel of Waziristan—an unknown priest from the small town of Ipi. Like the Mullah Powindah twenty years before him, he declared a holy war against the British and succeeded in eluding capture by hiding out in caves in Waziristan. He tested the endurance of the Politicals, Scouts, Army and Air Force alike; at one time or another, they were all involved in the attempt to catch the Faqir.

He had first started causing trouble in the mid-thirties in what came to be known as the Islam Bibi case: a! young Hindu girl was abducted by a Muslim and converted to Islam. The case went to court and the ruling went in favour of the Hindu; but sentiment was on the side of the Muslim. The first hostile demonstration was led by the Faqir of Ipi, at that time an obscure holy man whom the British could not have expected to rise to such notoriety. But after he and his following of no more than a thousand men started making large-scale attacks on troops, destroying bridges and cutting down telephone wires, military action was seen as the only solution.

A major operation of Scouts and Army was mounted ‘to sniff him out’ with the help of the Air Force. ‘There’s a ruddy war on but you’ll have got it from the BBC before this is posted,’ Jack Lowis wrote to his sister in November 1936. ‘It looks like a big show and I’m afraid the Mahsuds of the Shaktu valley are sure to join in’. As it happened, the fear of war abated temporarily. In January 1937 Lowis wrote: ‘The Faqir is still at large, though he has been completely inactive for some time as he is ill (with pneumonia). Military opinion, of course, is that he should be hounded and hunted, but then they either don’t realise or don’t believe that the hunting of Faqirs merely prolongs and enlarges the war and never by any chance results in the capture of the Faqir’.

John Prendergast recalled how on one occasion the Tochi Scouts synchronised an expedition with the South Waziristan Scouts to catch him. ‘We found the ashes of his fire still warm in a cave, but he had flown. Our informer, as usual, had informed both ways’. As with any operation against the tribes, the British could not expect to escape without casualties, and a political officer travelling with the Army could equally well be a victim.

At the same time the operation was a jaunt out which, providing all went well, most men would enjoy. ‘This war may go on for some time,’ Lowis informed his sister in May 1937, ‘and unless I blot my copybook I have every hope and intention of being with the column. I shall always be with the Brigade or Force HQ which is always the safest place, so kindly accept the situation in the same airy way that we always used to and rid your mind of anything but a sense of satisfaction that I’m having fun.’ It was, perhaps, only natural that Lowis should write to his sister in such terms.

She was, after all, Mrs Godfrey Meynell whose husband had been killed fighting the Mohmands two years previously with Goff Hamilton. Finally, with three brigades and strong Scout support, the expedition set off, ‘to smell out the Faqir who, of course will have left before we get there’. But this time the weather intervened, preventing the attack.

It was the worst hailstorm I’ve ever seen. Some of the stones were an inch in diameter—as big as walnuts—and it lasted twice as long as the usual spring storm. All the mules, camels and horses with the brigades stampeded, and most of the tents were flooded. In a show like this all tents are dug down about three feet as a protection against sniping so you can imagine the scene and the sort of witches’ cauldron that the tents were reduced to. We were lucky in ours, no mainstream came through to us and except for general dampness we are OK but many of the men and a lot of their stuff completely washed away, and all of it soaked. A lot of the supplies have been soaked and become unserviceable and what with one thing and another the war has been postponed for a day.

The objective was to bomb the caves—‘difficult and dangerous of access’—in which the Faqir had made his headquarters at Arsal Kot in the Shaktu valley. But, as Lowis pointed out,

‘blowing up a cave is apparently a difficult job. Your best efforts are apt merely to enlarge it to the subsequent satisfaction of the owner.

However, they made a really good job of it and collapsed the cliff and roofs on top of the lot of them.’ In his diary he noted: ‘Arsal Kot in ruins as result of aerial bombardment but some houses standing. By the end of day whole place levelled.’ Insofar as the caves were concerned, ‘We were all full of glamorous stories about the huge lashkars they had housed’ during recent months, but they turned out to be ‘disappointing little warrens’. Lowis went into the Vicarage—as the Faqir’s cave was called—and took a sackful of papers back which ‘didn’t prove to be of much use’.

As was to be expected, the Faqir himself had already escaped in good time, ‘very good time, judging from the hungry condition of the fleas,’ Lowis commented. ‘That evening it would not have been possible to affix a postage stamp to any part of my body without covering a bite. And they remained with me for the next thirty-six hours, fortunately in decreasing numbers.’ Lowis did not take much interest in the rest of the operation as he had caught a chill. ‘In fact I was asleep under a bush for most of it.’ The Faqir remained at large for several years.

From Arsal Kot he went to Gorwekht, near the Afghan border, where his activities worried the British during the Second World War. He died a natural death in 1960. Whoever wrote his obituary for The Times genially overlooked the irritation he had caused his pursuers, describing him as ‘a doughty and honourable opponent . . . a man of principle and saintliness . . . a redoubtable organiser of tribal warfare’.

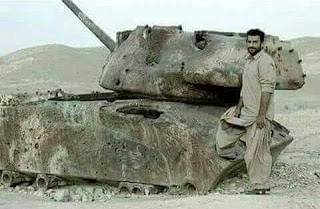

Later commentators, such as Milan Hauner, have been less sympathetic. ‘As a guerrilla leader he was uncompromising, unyielding, obstinate and unscrupulous in the choice of combat methods against his opponents. These included the traditional methods of tribal warfare such as ambush, kidnapping and mutilation.’ Not surprisingly perhaps, the Faqir’s son was reported to be fighting the Soviets in 1980s.

Mula Pawanda or Mulla Paiwanda.

From book.

Afghan Frontier At The Cross Road of Conflict.

betmatik

ReplyDeletekralbet

betpark

tipobet

slot siteleri

kibris bahis siteleri

poker siteleri

bonus veren siteler

mobil ödeme bahis

JLFHE

hatay

ReplyDeleteığdır

iskenderun

ısparta

istanbul

KTJSBR